Perspective - Choose Your Lens (Core Post No 3)

How to quit costing yourself money and stress by viewing investing through the wrong lens.

Once you understand that you should focus on decisions that matter (Core post No 1), viewed within a proper context (Core post No 2), it’s time to move on to choosing your lens—your decision-making perspective.

To illustrate, take a moment to answer the following:

How has the stock market performed?

How do you expect it to perform in the future?

Admittedly, the most common answer might be, “I haven’t got a clue.” To the extent you do have an answer, where did it come from? Did you do your own evaluation, or go with what you’ve heard in the financial media?

But that isn’t the point of the question. The critical question is: did you consider a specific time frame when answering the question?

Probably not.

You may have assumed we’re asking about how the stock market has performed so far this year. And, perhaps, how it might perform over the rest of the year. You probably didn’t consider how it might reasonably perform over the next 20 years, which is far more important to the long-term investor.

The Wrong Lens

If there’s one thing that costs investors more money and unnecessary stress, it’s looking at long-term investing through a short-term lens.

The cost of viewing investing through the wrong lens is staggering.

Part of the problem is that we tend to think of a retirement portfolio as a single portfolio with a single goal: providing enough money for you during retirement. It’s a reasonable way to think, but it’s too simple.

Your retirement portfolio actually has two competing goals: provide income you’ll need in the near future and continued growth in order to provide income you’ll need down the road.

By simplifying this into one portfolio, it’s easy to miss the fact that we’re dealing with two different time frames: short-term and long-term.

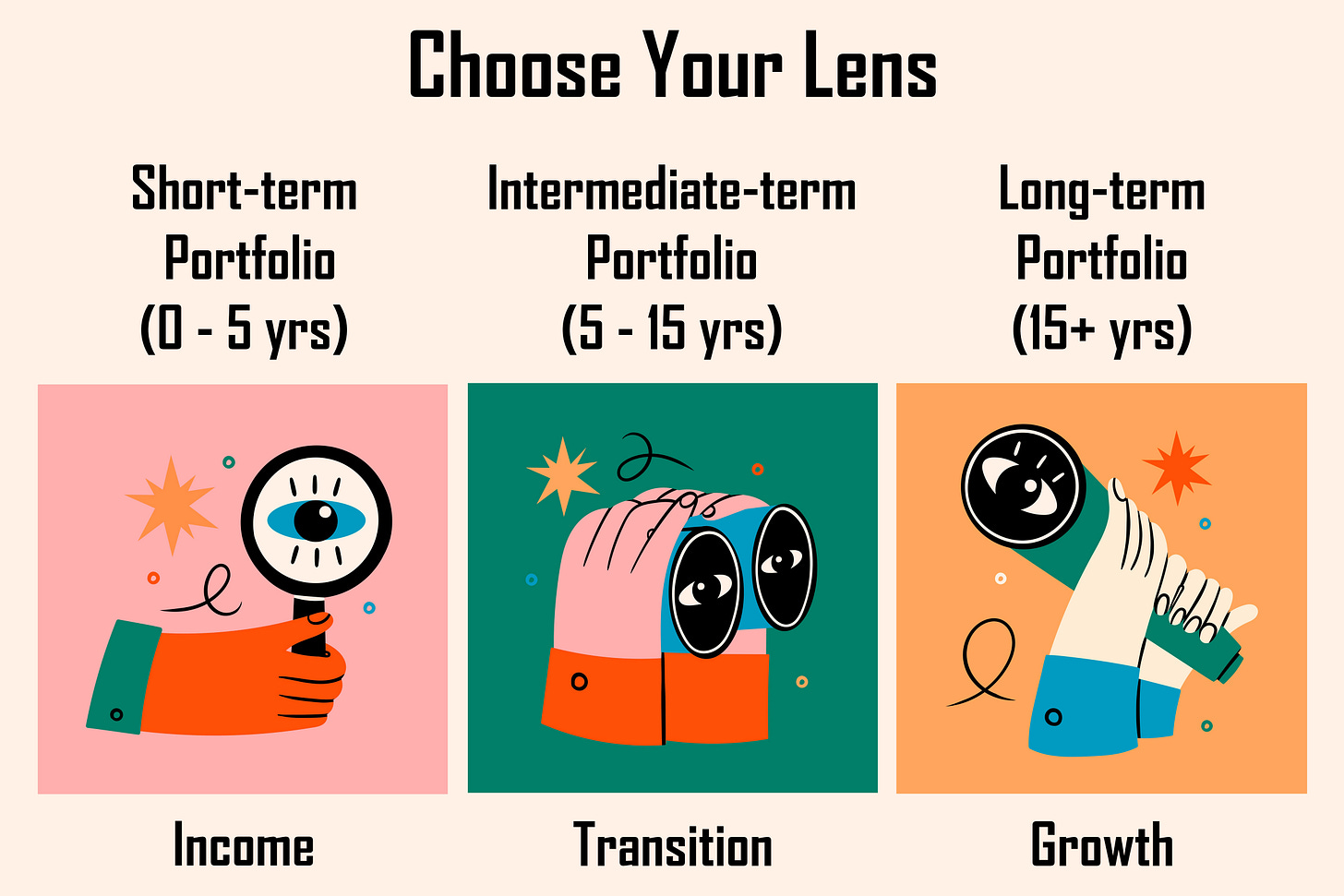

It will help if you begin to think about having a short-term retirement portfolio and a long-term portfolio (with an intermediate-term, transition portfolio in between).

Use the Least Risky Strategy for each Time frame

Let’s put this to work with a simple example in which you only have two investments to play with: a money market fund and a stock market index fund (say, the S&P 500 Index).

The goal is to choose the least risky strategy for each portfolio, using the following definition:

The least risky strategy is the one that gives you the best chance of winning.

Short-term Portfolio

The goal of your Short-term Portfolio is to provide income you’ll need in the near term. You want to protect against losing money and keep up with inflation.

So, what’s your choice, the money market fund or the stock index fund?

This one is probably obvious and makes sense. The money market fund is least risky and returns are generally close to the current inflation rate.

Long-term Portfolio

The goal of your Long-term Portfolio is to provide the growth you’ll need to ensure you have enough money further in the future. The real key here is to take advantage of compounding—the nearly magical way that money can grow if you give it time. You still want to avoid losing money, but this is through a long-term lens, say 15+ years in the future.

So, what’s the call? Which gives you the best chance of winning: the money market fund or the stock index fund?

This one is less obvious until you stop to think about it.

It’s crucial to compare the long-term compounding rate of the investment options. Historically, stocks have compounded at about 10% annually while money market funds have been closer to 3%. In terms of potential future wealth, this difference is stagering (potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars or more).

Note that these averages play out over longer periods than 15 years, but we’re using 15 years as the start of what you can consider “long-term.”

And, of course, we mentioned that you don’t want to lose money. The good news is that stocks (S&P 500) have yet to experience a 15-year or longer period when they have lost money. They will go up and down over shorter periods, but 15 years is enough time to ensure they recover.

The conclusion: stocks are the least risky strategy for your Long-term portfolio.

The Quick Takeaway

We’re just touching the surface here and will cover this topic in more detail in future posts. For now, simply understand that viewing long-term investing through a short-term lens often leads to overreactions that have the opposite effect of what you hope. What seems like a way to make your portfolio less risky actually makes it more risky in the long run—i.e., it reduces your chances of having enough money in the future and causes unnecessary stress.

Stuart & Sharon