A Brief History of Wall Street and the New York Stock Exchange (Core Post No 6)

Why it's called Wall Street and other curious facts about the home of the stock market.

In 1653, if you walked north from the tip of New Amsterdam, you’d eventually run into a 12-foot-high wooden stockade stretching across the island from the East River to the Hudson River (in the map below, north is to the left). The wall was intended to protect the Dutch from attacks.

Roughly ten years later, after being captured by the British, New Amsterdam was renamed New York.

The Brits were good at building roads and, about ten years after taking over Manhattan, a new road was laid out beside the stockade wall.

The road was, fittingly, called Wall Street. (Today, Wall Street no longer crosses from river to river but rather from the East River to Broadway.)

Many years later, the seed of a Conocarpus erectus, commonly called a buttonwood tree, took root next to the road, beginning its march toward immortality.

The Buttonwood Agreement

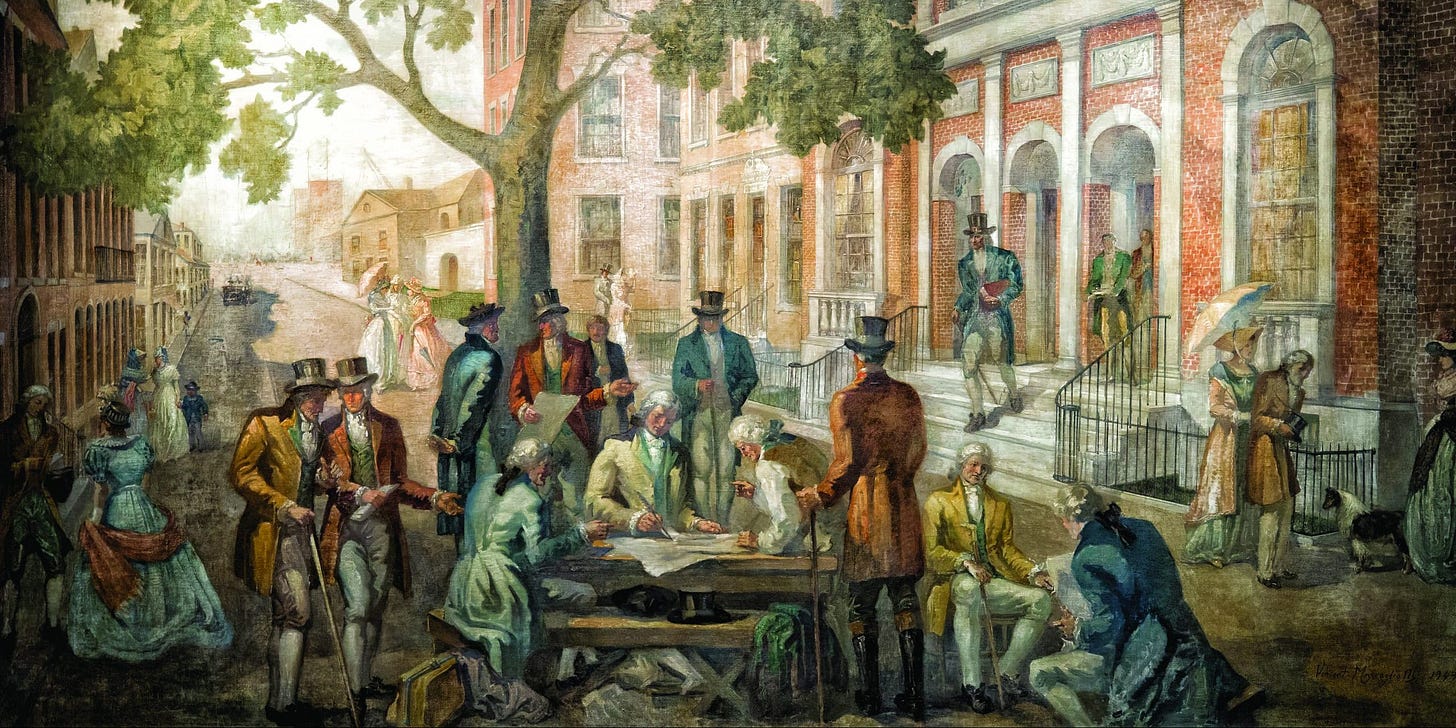

By 1792 our tree was fully grown and stood witness (according to Wall Street folklore) to a gathering of 24 brokers who agreed to trade securities on a common commission basis. The “Buttonwood Agreement” is considered to be the birth of the New York Stock Exchange (although the New York Stock & Exchange Board, as it was initially known, wouldn’t be officially founded for another 25 years).

Today, a painting capturing the moment resides at the New York Stock Exchange.

The Financial Wild West

It’s useful to understand that the early years of the stock market were nothing like the stock market of today. For one thing, the word stock was used more broadly, basically describing any tradeable security.

Large, global companies like Apple and Microsoft didn’t exist.

The first publicly traded security was $80 million of government bonds, issued in order to refinance all federal and state Revolutionary War debt. The plan to refinance the debt at face value, proposed by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, was not popular in southern states. To win approval, Hamilton approached Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, a prominent southerner, agreeing to a compromise in which Jefferson supported Hamilton’s plan to issue the bonds while Hamilton supported Jefferson’s plan to move the seat of the federal government from New York further south to Philadelphia (while the city of Washington D.C. was being built).

The early years of the New York Stock Exchange were dominated by trading in the securities of railroad companys. The first stock traded on the exchange was Mohawk & Hudson in 1830. Over the course of the next fifty years the growth in railroads and trading in railroad stocks and bonds boomed.

Charles Dow’s first index was not the Dow Jones Industrial Average that you hear about on a daily basis, but rather the Dow Jones Transportation Average, first published twelve years earlier. Nine of the eleven stocks in the index were railroad stocks.

Incidentally, Charles Dow’s partner Edward Jones (not related to the financial firm today) had nothing to do with the creation of the Index. The two, along with a third partner Charles Bergstresser, founded Dow Jones & Co. in 1882. They felt Bergstresser’s name was too long to fit in the company title, so he missed out in having this name immortalized in the Dow Jones Index.

Working out of a basement next door to the New York Stock Exchange, Dow Jones & Co. published a brief market summary called the Customer’s Afternoon Letter, which was later renamed The Wall Street Journal, a name which Jones did come up with.

The securities being traded at the time were highly speculative and susceptible to price manipulation, aided by the fact there was no formal requirement for reporting accurate information about the securities. It was the financial equivalent of the wild, wild west.

To the extent there was information, the lack of communication options further inhibited smooth and fair trading.

Flags, Pigeons, and Ticker Tapes

Today, we can pull out our phones and find the price of any publicly traded stock instantly, along with as much financial data and analysis as we want—probably too much information.

Not so in the early days of the stock market. One of the earliest attempts to communicate stock prices between New York and Philadelphia involved agents with flags and telescopes positioned on hills and buildings every six to eight miles who would signal the opening price of each stock. Can you imagine having that job on a cold and rainy day?

Perhaps stranger still, in the 1850s, carrier pigeons were used to take summary reports from US-bound European steamers to Boston where news of the world could be passed on to subscribers of the service. It was worth paying to get information sooner. This method of communication was overtaken by the laying of the trans-Atlantic cable in 1886.

Communications continued to improve at a rapid pace.

One year later, in 1867, former telegraph operator Edward A. Calahan invented the stock ticker which disseminated stock price information to offices throughout lower Manhattan.

Bigger still, on March 10, 1876, Thomas Watson, assistant to Alexander Graham Bell, heard the words, “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.” The telephone had arrived.

Two years later, the first telephone was installed in the New York Stock Exchange making the dissemination of market news much more efficient.

Pieces of Eight

Incidentally, do you know what stock prices, until fairly recently, had to do with Long John Silver’s parrot Captain Flint?

The Piece of Eight was made famous in pirate folklore when Robert Louis Stevenson published his novel, Treasure Island (the cabin boy Jim later recounts a disturbing dream in which the parrot is screeching, “Pieces of Eight, Pieces of Eight”).

The term actually refers to Spanish dollars which were frequently divided with hammer and chisel into eight pieces. The Spanish dollar, initially minted in 1497, became the standard of monetary value in the colonies and was the coin upon which the original United States dollar was based. It remained legal tender in the United States until the Coinage Act of 1857.

What does this have to do with stocks?

Since early stock traders were often also merchants, it was only natural that they quoted and traded stock prices in eights of a dollar, similar to the pricing convention for merchant goods.

Stock prices continued to be quoted in eights until finally switching to decimals in 2001.

The Crash and Reform

Beginning in 1923, the stock market embarked on a historic six-year bull market, epitomizing the “roaring 20s.” By 1928, speculative buying and buying on margin pushed the market higher.

The market reached its peak in September 1929.

On September 5th, 1929, economist Roger Babson warned, “Sooner or later a crash is coming, and it may be terrific.”

His warning came true beginning on October 24th (“Black Thursday”) and continued over the course of the next five days.

Crowds filled the streets and panic ensued. Investors (speculators?) who bought stocks on margin were totally wiped out—though the story of investors jumping out of buildings is inaccurate.

The stock market decline continued for three years and by the low point in 1932, the Dow was down 89 percent from its 1929 peak.

By the time Franklin Roosevelt was inaugurated as president in 1933, the Great Depression was fully under way, the result of the stock market crash and a series of broader economic problems.

Roosevelt promised a “New Deal” to get the economy back on track, leading to the Banking Act of 1933, the Securities Act of 1933, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (which established the Securities and Exchange Commission—the SEC).

Since these guardrails were put in place, volatility in the stock market has declined significantly. The monthly volatility in the stock market for every decade since the 30s has been less than half the level of volatility during the 1930s.

And while the return for the decade of the 2000s—which included the bursting of the dot-com bubble and the financial crisis of 2008—was actually lower than the 1930s (-.95% vs -.05%), it was nowhere near as volatile.

More recently, the pandemic-related stock market decline from December 2021 through September 2022 was eclipsed by the subsequent quick recovery leading to new record highs by December 2023. The guardrails were working.

The Stock Market Today

If you visit New York today and head to the financial district, you’ll likely find yourself standing in front of the New York Stock Exchange (as we are shown in the photo below). You may be surprised that you’re actually standing on Broad Street, not Wall Street (there is an entrance to the Exchange from the back corner of the building at 11 Wall Street).

The stocks traded on the NYSE today are U.S. companies but, in reality, they are global companies. It’s no longer the financial wild, wild, west of 100 years ago.

Today’s stock market offers investors, including millions of Americans investing via corporate 401(k) plans—a way to easily participate in the collective success of businesses driving the global economy.

Stocks are still volatile today, especially in the short run, but, as we’ve noted in other posts, the risk of owning stocks declines over successively longer holding periods. Due to their high compounding rate, stocks are the least risky investment—they give you the best chance of achieving your financial goals—for the long-term investor.

More History?

Our goal with this post was to simply share some interesting stories and facts about Wall Street and the New York Stock Exchange.

If you find these interesting, we recommend the book, The New York Stock Exchange: The First 200 Years, which includes numerous historical photos and from which some of these stories were extracted.

Stuart & Sharon